(This post was first published on the Romance Junkie blog as part of my RECKONING blog tour)

For a genre by and large written by women for women, romance uses a lot of sexist tropes in its storytelling. You can’t swing a pink dildo around the romance section of your favorite bookstore without hitting a paperback that denigrates women in some way, and I’m not just talking about the Old Skool stuff.

I get where the impulse comes from. The genre’s purpose is to sell a romantic fantasy, and often that fantasy entails willowy women being swept away by alpha males as a metaphor for losing oneself in sexual and/or romantic pleasure in a way many of us can’t do in real life.

If the basic definition of feminism is treating men and women as equals, then the woman-swept-off-her-feet-by-a-manly-man naturally caters to the opposite impulse by playing into our desires to abdicate our mundane responsibilities and let somebody else take charge—without the negative consequences that often follow in real life, of course.

Not to say it’s an unreasonable desire to build a fantasy around. Who doesn’t want a Greek billionaire to worship them? But as the late Roger Ebert said about movies—“It’s not what a movie is about, it’s how it is about it”—it’s not what a romance novel is about, but how it goes about it. By dipping a toe into the pool of anti-feminism in service of a romance storyline, some books trip headfirst into it and send up a maelstrom of cringe-worthy sexist stereotypes, and sometimes outright misogyny.

(Note: “sexism” is a prejudice or stereotype based on gender; “misogyny” is a dislike or hatred of females. Not surprisingly, the two often go hand-in-hand)

Here are the three biggest offenders that need to follow shirtless-mullet-heroes and he-raped-me-until-I-loved-him-heroines into the Romance Pit of No Return:

– Slut-shaming

God forbid a woman should be sexually experienced…or, even worse, if she enjoyed that experience…or—the worst—if she dares to have sex with a man other than her intended during the story, no matter the circumstances! Virginal heroines are a trope all their own, along with the idea that the state of a woman’s hymen is somehow directly proportional to her worth. Of course men aren’t held to this standard. Dudes can ho around all they want, it don’t mean a thang! But a lady, especially the heroine, must save herself for The One. And if she doesn’t…for shame.

*A woman’s value = what her vagina’s been up to.

– All other women in the story are evil and/or sluts

Basic decency is a zero-sum game, and other women are the enemy. What better way to make the heroine look good than by bringing down all the other ladies around her? Her true love will only want her if she’s not like other women, i.e. a not a slut (see above).

*A woman’s value = how she compares to other women.

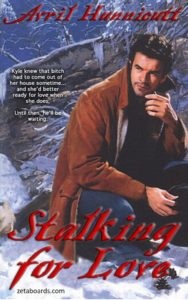

– Stalking/abusive behavior portrayed as romantic

He shows up at her work unannounced and demands she go places with him. He makes proclamations about how “she will be his,” orders her around (especially in the bedroom), won’t take no for an answer, won’t let her deal with her own problems, and won’t let her make her own life decisions…because he loves her so much! She may tell him no, but her heart says yes. It’s okay, though, because he knows what she wants. If he keeps telling her she’s beautiful and assures her that he’s never felt this way about anyone else before, she’ll just keep swooning no matter what he does.

* A woman’s value = what a man tells her it is

Obviously not all romance novels contain sexist elements; in fact, many are happily, proudly feminist! And you could argue to each their own—these books are fiction after all. A lot of women like the anti-feminism fantasy, so what’s the harm? The problem is that fiction is a reflection of reality as the author sees it, if only in subtext. If a certain genre of fiction contained, for instance, regular allusions to anti-Semitism, what assumptions would you make about the people who read it? If we tolerate a consistent thread of sexism and misogyny in our beloved genre, what does that say about us?